In looking for a public link to this I couldn’t find one handy, so I’m positing this now.

Thriving After Fire – Rare plants and the biologists who search for them

Fire Adapted Hudsonia montana, mountain goldenheather, thrives after wildfires on Shortoff Mountain in the Grandfather Ranger District. Cooperation between the US Forest Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service, and The Nature Conservancy helps document their persistence following spring fires.

Three liters of water barely made a dent in my thirst the first hot September day of monitoring rare plants on Shortoff Mountain. So, the second day I brought 4 liters and an umbrella to create my own shade. As we walked in silence, dripping with sweat, back down to the truck, my pants were shredded at both knees from crawling through thorny brush and my umbrella was broken on one side. But I was smiling.

Earlier that day we had spent hours walking near the edge of Shortoff Mountain in Grandfather Ranger District looking for – and finding in abundance – Hudsonia montana. This scrubby little plant, commonly known as mountain golden heather, clings to the rocks almost as close to the edge of a cliff as one can get. It’s a dare devil plant sending USFS botanist, Gary Kaufman, into billy-goat mode as he very carefully picks his way up the cliff side counting plants.

Our goal was simple: use the maps created previous years to visit the areas on Shortoff mountain known to have the golden heather, count the patches of plants using a size-class system and help estimate their current numbers. But why do this now, on a hot September day when summer seems never ending? Because the plants were burned earlier this year by wildfires and biologists charged with protecting this federally listed species need to know the impacts of the fire.

Shortoff mountain has burned on average at least once every decade for hundreds of years. It’s prominent rock outcrops, Table Mountain pine, and bunchgrasses are adapted to the frequent lightning-ignited fires. The little plant we were looking for, Hudsonia, is no different. It thrives in this fire adapted ecosystem and has found its niche, only growing in two counties in North Carolina. In past years there have been dramatic increases in the plants post-fire. It’s kind of like how cutting your grass with a lawn mower helps the grass grow back thicker. Except in this case, Hudsonia grows back after fire and creeps further into and over neighboring rocks and mossy areas.

Once we got back to the truck the second day, botanists from the USFS and US Fish and Wildlife Service planned to come back for a third day to sample a few more areas of plants. What we had seen so far was promising, as expected the Hudsonia as well as other fire adapted plants like little bluestem were growing well. I hope you enjoy this short video showing the Hudsonia and the plants on Shortoff thriving after the spring wildfire.

Crawley Branch Southern Yellow Pine Restoration Project

Guest Post by Jake Lubera, Grandfather Acting District Ranger

There is a national recognition that insects and disease have had a long devastating effect on the American Landscape. Today we think of insects such as Hemlock Woolly Adelgid, Southern Pine Beetle, and Emerald Ash Borer and the changes in ecosystems that they have and may still cause. This type of change of ecosystems due to insect and disease has been seen before. Just look back to the days of Chestnut Blight and the changes to the landscape that caused. The difference between then and now is that working in a collaborative process we have tools in place to react quicker to manage the infestations and make the landscape more resilient to outbreaks in the future.

Using the authorities provided by the 2014 Farm Bill amendment to the Health Forest Restoration Act of 2003, The Grandfather Ranger District has successfully worked hand in hand with local partners to identify the Crawley Branch area in Caldwell County as potentially susceptible to Southern Pine Beetle with the goal of making them more resilient to future outbreaks. This completed planning effort has been done in conjunction with the ongoing restoration efforts associated with the Grandfather CFLR project. By using this collaborative framework established under the project and the best available science we will be able to be proactive rather than reactive to devastating insects and disease.

The authorities derived from the 2014 Farm Bill are some of the tools we have to deal with insects and disease. With that in mind let’s play pretend. Say you are wanting to hire a contractor to build a house. Two different contractors meet with you to discuss your design. Both are very knowledgeable of the designs. The difference is one has a tool box consisting of a just a hammer and a screw driver. The other has a full complement of tools, each with a specific use for a specific need. Just as if you were building a house, you are more likely to succeed in restoration and resiliency efforts if you have multiple tools to get the work done. Farm Bill authorities, Stewardship contracting, and Good Neighbor Authorities are just some more very useful tool we have to meet a specific need on the landscape. It is when we use all the tools in the tool box, including collaboration with the public, that we can manage the landscape to allow it to be resilient to future outbreaks.

View the Crawley Branch project documents here.

Black Bears and Forest Management on the Grandfather

Despite our unprecedented warm weather this winter, most of Western North Carolina’s black bears are sleeping deep right now, and some females have just recently given birth. Bears are among the most charismatic species in the eastern U.S., and bear ecology is pretty fascinating. The WNC bear population is super healthy and we are learning much more about their movements, habitat needs, and tolerance for living around people.

I’ve given this presentation several times around WNC now, but I’ve been working to turn it into an article others can access.

More about bears ecology in western North Carolina and how the Grandfather CFLR project impacts bears.

SAWS Restores Trails in Harper Creek

Southern Appalachian Wilderness Stewards’ (SAWS) Central crew spent 6 days from July 8 to July 13, 2016 on the Pisgah National Forest in the Harper Creek Wilderness Study Area (WSA) working on the North Harper Creek (#266) and North Harper Creek Falls trails. Altogether the crew worked on about 1.5 miles doing a variety of trail work. This included 1277 feet of brushing to open the trail corridor, the removal of 15 trees from across the trail, digging 19 drains/grade dips for erosion control, installing 4 rock steps, and re-establishing 335 feet of tread. The crew also worked to close 885 feet of social trails, to ensure that users are able to identify where the actual trail is. The 6-person field crew partnered with the Grandfather Ranger District to plan, scout and complete this project.

Wild South and Linville Volunteers Tackle Babel Tower Trail

This summer Wild South and Linville Area Volunteers, led by partner Kevin Massey, are hard at work doing some heavy maintenance on the Babel Tower trail in the Linville Gorge Wilderness. Helped out by an agreement with Wild South under the Grandfather Restoration Project, the crew is able to do some much needed work on one of the most popular trails within the Wilderness area.

Crews will be working hard out in the field this summer adding check dams and repairing drainage on steep sections of the trail, adding stone cribbing on heavily eroding sections, redefining the main trail and decommissioning user-created trails near the tower that are causing erosion into Linville River. This is one great example of partnerships in the Linville area and we are lucky to have an amazing group of partners and community volunteers who can steward the Linville Gorge Wilderness! Keep track of the progress on the Linville Gorge Maps blog at www.linvillegorgemaps.org.

Kevin’s great work in the Gorge was also recently highlighted in the Asheville Citizen Times article “Watching out over wild, picturesque Linville Gorge“.

Fire Learning Trail Launches

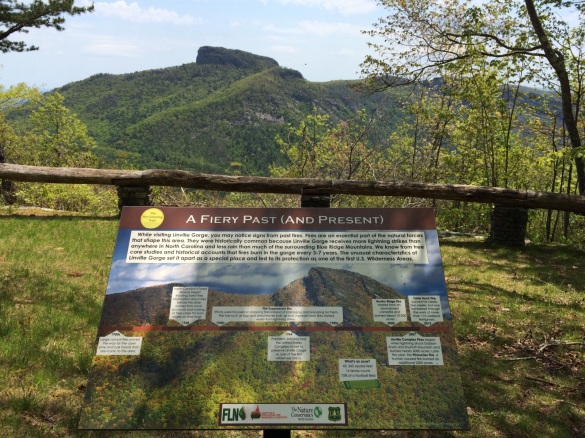

Visiting Linville Gorge on the Grandfather Ranger District of the Pisgah National Forest it is hard not to notice the signs of fire. From the iconic wind-whipped table mountain pines gripping the cliffs at the edge of the gorge, to the characteristic clear views, fire has shaped Linville from the beginning.

Partnering with The Nature Conservancy, The Fire Learning Network, and the Consortium of Appalachian Fire Managers and Scientists, the Grandfather Ranger District has installed a series of informational signs along Old NC 105 on the west rim of Linville Gorge to share with the public information about fire safety, fire history, fire ecology, and firefighting. Visitors starting at the Information Cabin at the north end of Old NC 105 can visit the signs by driving south along the Fire Learning Trail as they take in the sights of the area.

The signs are accompanied by a series of pod casts featuring radio-style interviews with local fire managers that are available on iTunes (search: Fire Learning Trail) or on CDs distributed free of charge at the Linville Information Cabin.

The Fire Learning Trail is part of an effort to increase education on the history of the Grandfather Ranger District and the forces of nature that have shaped the forests. Specialists from The Nature Conservancy and the Consortium of Appalachian Fire Managers and Scientists were on hand at the Linville Gorge Spring Celebration last weekend to talk to the public about this exciting new outreach effort.

What Does Restoration Look Like? Saving Hemlocks

Hemlock Preservation from Lisa Jennings on Vimeo. This highlight is part of a series of videos celebrating the mid-point of the Grandfather Restoration Project to provide folks with an inside view into what restoration looks like in the forest.

One of my favorite camp sites when I was younger was in a hemlock grove deep in the Wilson Creek watershed, where I could cool off under the emerald green canopy and the hemlock needles were so thick that I could sleep comfortably on the forest floor. Going back to that site today, it is much different from the magical place of my memories. Now, those towering green hemlocks are dull, grey, and leafless. The forest floor is littered with fallen branches and toppled hemlock trees.

In the last decade there has been a drastic change in the forest communities of the southern Appalachians. Hemlock woolly adelgid, a small aphid-like insect from East-Asia, has decimated hemlocks in eastern North America. First introduced in a private garden near Richmond, Virginia, the adelgid has spread both north and south – from Georgia to New England.

The adelgid attaches to the base of the hemlock needles, where it feeds on the sugars that are being transported from the needles to the tree. Infested trees can be identified by the white woolly mass on the underside of the branch. Over time the adelgid starves out the hemlock, leading to defoliation and eventually death.

Signs mark treated Carolina hemlock trees

Scientists have yet to find resistant hemlocks in the east, leaving active treatment as the only option to save these iconic trees. Maintaining hemlock forests is one of the main goals of the Grandfather Restoration Project, an 8-year collaborative project to restore 40,000 acres of forest on the Grandfather Ranger District as part of the national Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program. Two species of hemlocks grow on the Grandfather District. The more common eastern hemlock grows in streamside forests. The rare Carolina hemlock grows on rocky outcrops. Both species are susceptible to the hemlock woolly adelgid.

The most common way to treat hemlocks for the adelgid is using an insecticide treatment. The Forest Service’s primary chemical of choice is called Imidacloprid. Imidacloprid is mixed with water and injected into the soil around the root system of a hemlock. The chemical moves into the foliage, killing the adelgids as they feed but leaving the foliage unharmed. This both maintains old hemlocks and supports regeneration of new hemlocks near the treated trees.

The other way to treat the adelgid is using a natural predator. Laracobius negrinus, a small beetle from the Pacific Northwest, is a natural predator of the hemlock woolly adelgid. Scientists at the Southern Research Station are studying how these beetles respond to the colder winters in our area, and how we can best use them.

Through the Grandfather Restoration Project, the Forest Service has treated thousands of hemlocks and partnered with leading researchers to release beetles at about a dozen locations on the Grandfather Ranger District. Although we cannot save every hemlocks, we can help preserve the species to ensure this iconic tree remains a component of the forest into the future.

Rose’s Mountain Prescribed Burn

This was the first ever burn at the Rose’s Mountain unit, which was the first unit to be burned under the new Grandfather Restoration Burns project. The ecosystem in this unit is highly fire-adapted, and was a top-ranking area to prioritize burns under the project. We had a great burn, blackening 70-80% of the unit, and meeting all objectives. Fire managers were able to keep the flames low in young pine areas to protect their growth. Firefighters also protected the Mountains to Sea trail, which received no damage in the burn. Thanks not only to our firefighters on the ground, but to all the collaborative members who helped guide the Restoration Burns project! We are excited to be able to restore these areas. This unit in particular has Fire Learning Network vegetation monitoring plots that will be monitored under the CFLR agreement with Western Carolina University.

Date: March 9-10

Size: 3,100 acres

Location: North of Morganton, NC, South of Table Rock

Purpose: Restoration of fire-adapted communities, fuels reduction

Partners: The NC Forest Service, The Nature Conservancy, North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, North Carolina Department of Transportation, and Burke County Emergency Management

What Does Restoration Look Like? Shortleaf Pine at Roses Creek

Shortleaf Restoration from Lisa Jennings on Vimeo — part of a series of videos on restoration celebrating the mid-point of the Grandfather Restoration Project.

Forest restoration is something that is talked about a lot these days. But what does restoration really look like on the ground? 2016 marks the halfway point in the project. In the past 4 years, Forest Service managers have been working with a group of partners to improve forest health on over 27,000 acres. One of the key projects the Forest Service has led is the shortleaf pine restoration work at Roses Creek, near Morganton, NC.

Shortleaf pines are a southern yellow pine that grow at lower elevations on the rolling slopes where the foothills meet the Appalachian Mountains. Shortleaf pine forests contain not only shortleaf pines, but a mix of oak species that benefit wildlife as well as other southern yellow pines. The stands are typically open – more like a woodland than a dense forest – and contain a rich understory of grasses and forbs. Historically, shortleaf pine forests were common on the dry, south facing slopes of the Grandfather Ranger District. Today, they are scattered across only a small percentage of the district.

Past records show that this forest type supported a wide variety of plant and animal species. Shortleaf pine forests in the Southern Blue Ridge once supported rare species like red cockaded woodpecker as well game species like bobwhite quail. But, the forests were hit hard on several fronts. First, much of the forest was lost with land clearing – which was common on these rolling slopes in the early 1900s. Next came fire suppression – without frequent fire the fire-loving oaks and pines were overtaken by yellow poplars and maples. The final hit was the southern pine beetle outbreaks in the 1990s which swept through the area, killing many of the remaining shortleaf pines.

The Roses Creek shortleaf pine restoration site provides an opportunity for these pine forests to come back to life. Last year, the Forest Service brought in local loggers to do a restoration harvest. Select yellow pine and oak trees were left in the overstory to provide structure and a seed source. After the harvest, the Grandfather Ranger District fire staff conducted a prescribed fire to prepare the seed bed. Southern pine seeds germinate best where there is little leaf litter, and burning will knock back some of the competing trees and shrubs. The final step is planting shortleaf pine seedlings in between the remaining trees to add to the seed source from the few existing shortleaf pines.

The Roses Creek site is just one example of shortleaf pine restoration under the Grandfather Restoration Project. Managers are working to restore the system so that rare plants and animals will return to the area, and future generations will be able to enjoy the unique and beautiful shortleaf pine forests.