The call came in at 3pm on a clear, hot Saturday in the middle of July: “We’ve got a report of smoke on Bald Knob north of Lake James.” For those of us responding that day, we had no idea we would be working on the wildfire in the summer heat for nearly a month.

Smoke visible just west of Bald Knob

As a firefighter for Pisgah National Forest’s Grandfather Ranger District you become intimately familiar with the lay of the land. Some areas evoke fond memories – rolling hills, majestic forests, bubbling brooks. Bald Knob is not one of those areas. The terrain west of Bald Knob is unforgiving. Steep slopes end in sheer cliffs. Thick evergreen shrubs and piled downed trees force you to crawl on hands and knees to get around.

But the area around Bald Knob was not always so unforgiving. Decades of fire suppression and widespread damage from the southern pine beetle outbreak of the late 1990’s changed the structure of the forest. What was once pine-dominated woodland with an open, grassy understory became choked with ingrowth over the years, leading to dangerous wildfire conditions.

Responding to the wildfire that hot, July afternoon, fire managers had a tough decision. Do you send your firefighters miles off trail to dangerous conditions to suppress a lightning fire in an ecosystem where fire would naturally occur? Or do you fall, back, manage the fire, and risk it moving towards private property?

Managers ultimately decided to manage the fire, allowing it to move naturally through the terrain. There was one key consideration that played into the decision – the existence of prescribed fire restoration units on the west, south, and east sides of the fire.

The decision lay with the District Ranger, Nicholas Larson. “We realized from start that this ignition was in a very difficult place to access. Considering the heavy fuels and inability to use equipment in this type of terrain we knew suppression tactics would have a low probability of success,” Larson said. “Pair all that with the fact that we have restoration treatments all over this ridge and it really was a great opportunity to step back and think about the appropriate response.”

Lake James Prescribed Fire – January 2015

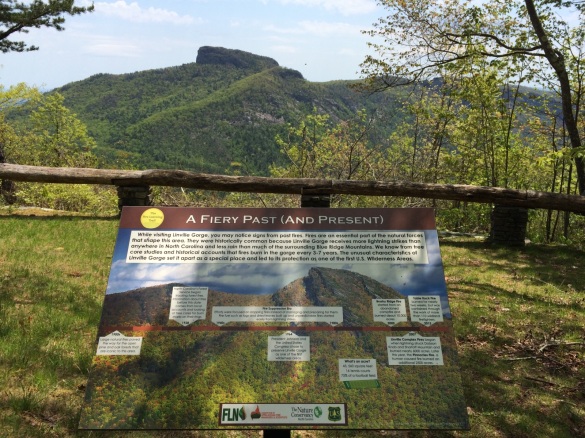

Prescribed fire has been used as a tool to reduce wildfire risk and restore forest structure in the Southern Appalachians since the mid 1990’s. In fire adapted areas like Bald Knob, wildfire would historically occur every 5-10 years, reducing fuels from leaf litter, sticks, and logs that build up over time. These natural wildfires have been suppressed since the 1940’s.

Under the Grandfather Restoration Project, part of the Forest Service’s Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program, the Grandfather Ranger District has increased the number of acres managed for fuels reduction 6-fold. Recent prescribed burns around Bald Knob were critical in slowing the spread of the fire. These treatments allowed the response to this wildfire to be one that focused on restoring fire adapted ecosystems and reducing fuels, without putting firefighters at risk.

Fire activity increased on the Bald Knob Fire as the long, hot July days crept into August. The prescribed fire units on the west, south, and east sides allowed firefighters to focus on keeping the fire off private property on the north end of Bald Knob. When the rains finally came in mid-August, the fire had burned over 1,200 acres. No structures were lost. No firefighters were injured.

Last week the Forest Service released a report detailing the effectiveness of the surrounding fuel treatments in managing the Bald Knob Fire.

With increased population growth in the Southern Appalachians, prescribed fire will continue to be an important tool in preventing wildfire spread. The Forest Service prioritizes burns where they can do the most good to reduce fuels, restore structure, and minimize risk to private property. We live near our National Forest because it provides the perfect setting for a mountain home. No one wants to lose their home in a wildfire. As we move into the winter fire season, rest assured that managers are out in the woods proactively fighting wildfire through fuel reduction treatments, restoration, and prescribed fire.